LIBRARY LIST

An experiment in reading

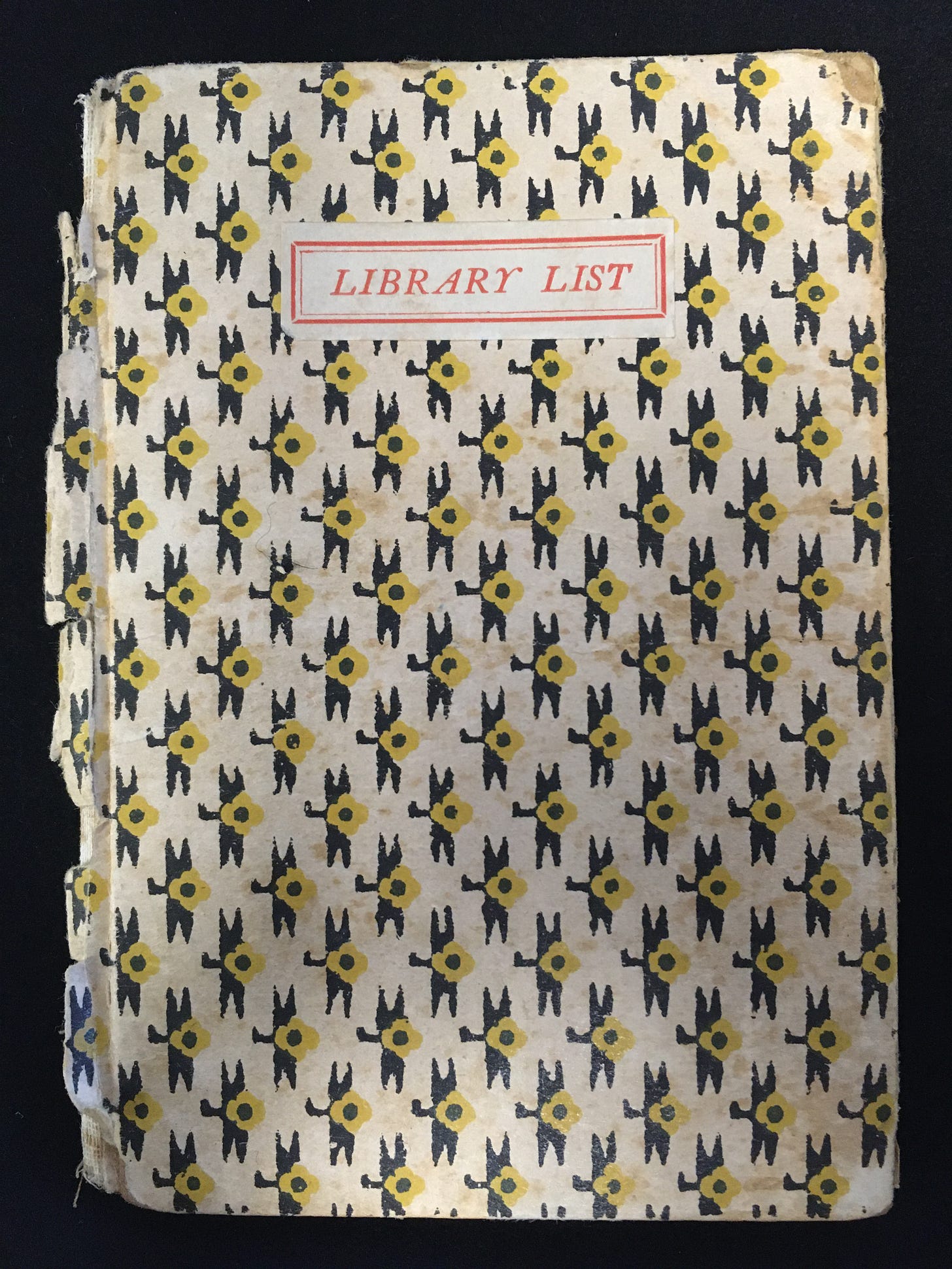

About six years ago I inherited a small, paper-covered book. Approximately 9.5cm by 13cm, it is printed all over with a repeating design in black and yellow: a four-petalled yellow flower with a black eye and a stylised, spiky leaf, like rows of little biplanes seen from below. Pasted to its front cover is a label. In slanting, seriffed red capitals, it reads LIBRARY LIST.

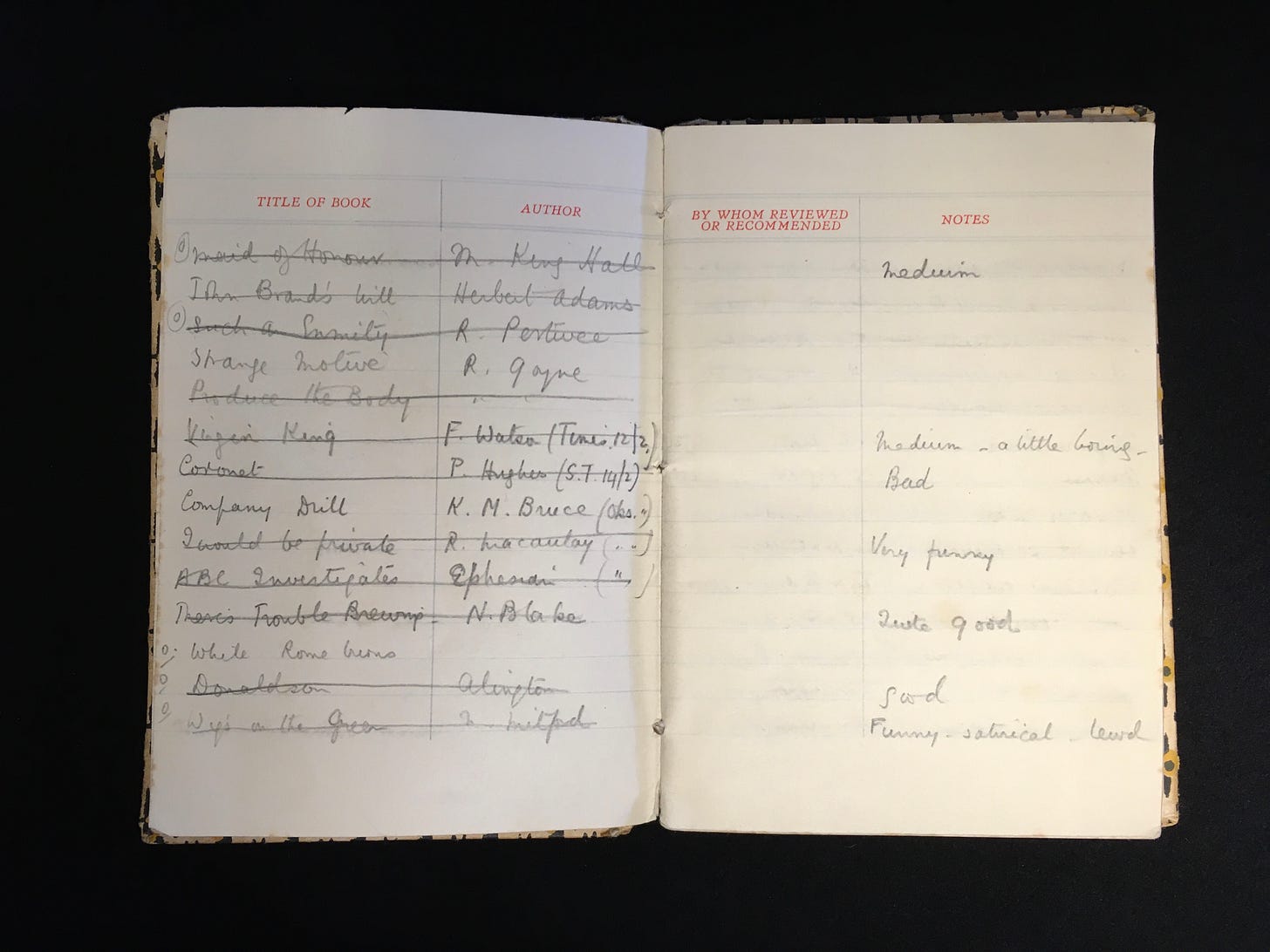

Inside, in neat pencil, and sometimes fountain pen, is a list of authors and titles, and a set of wry notes: ‘Medium - a little boring’, or, ‘Funny - satirical - lewd’.

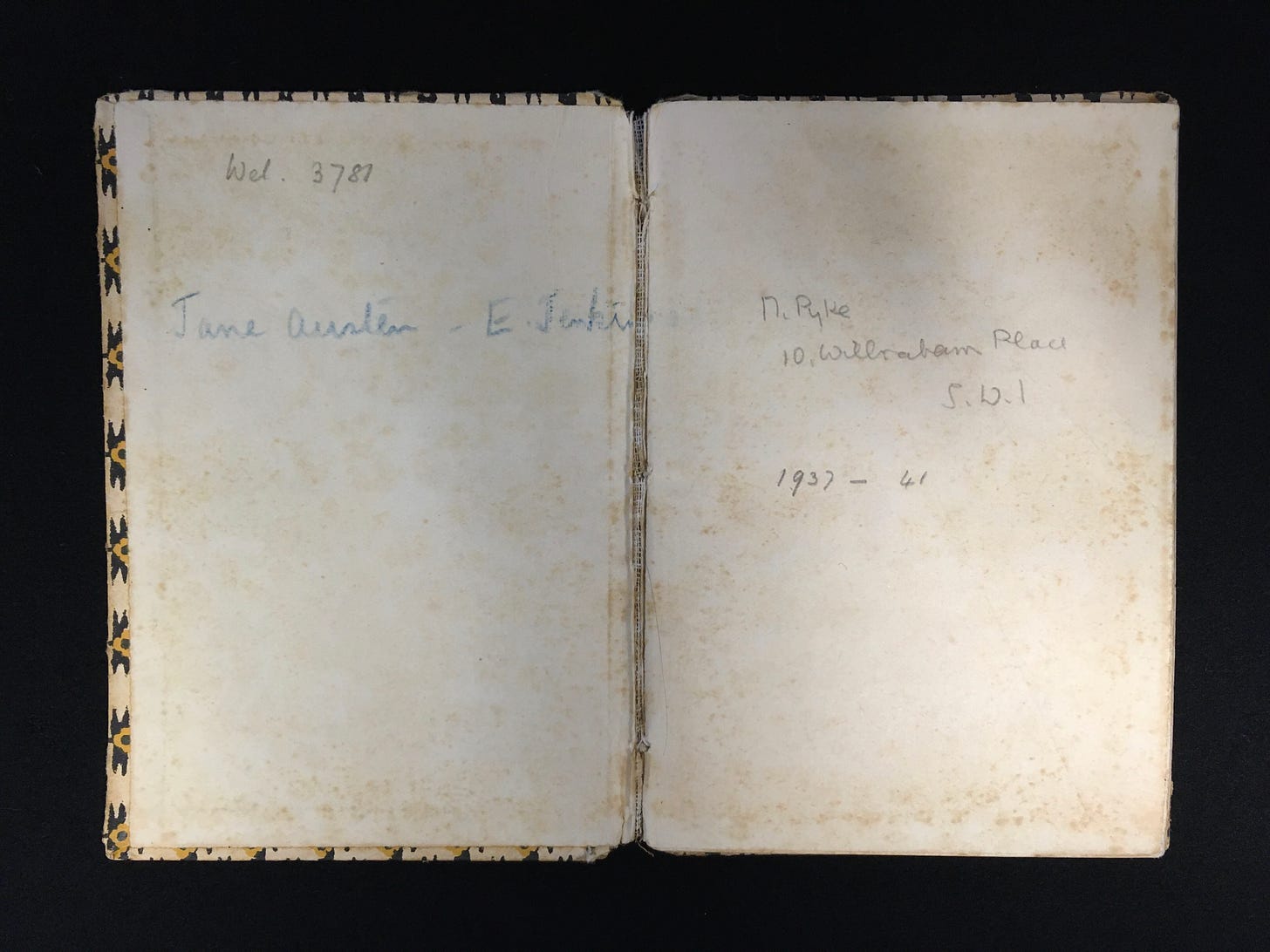

On the fly-leaf, in the same small, tidy hand, it is dated ‘1937-41’.

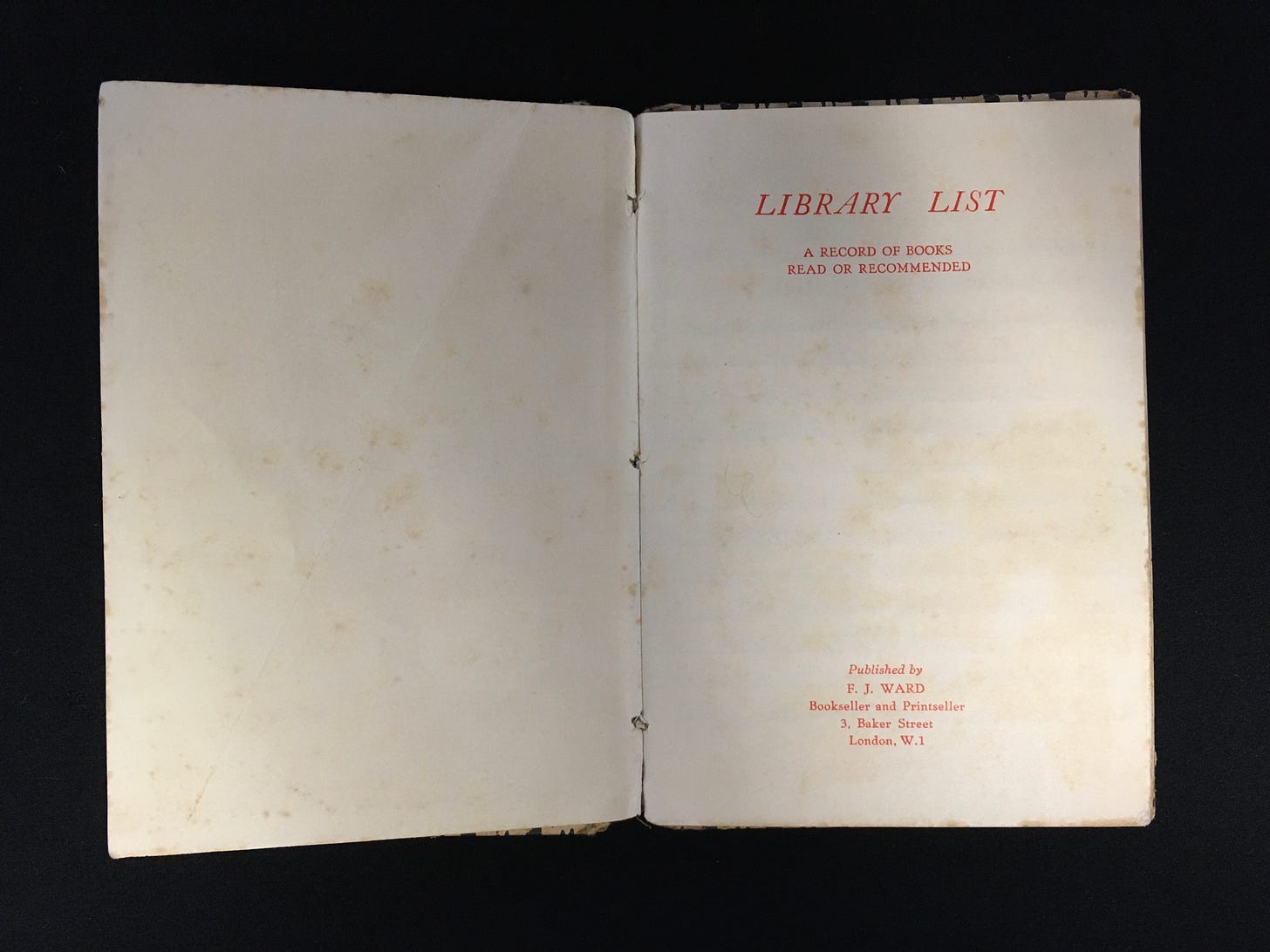

It is ‘A record of books read or recommended’ and it was published by F.J. Ward, ‘Bookseller and Printseller, 3, Baker Street, London, W.1’ It belonged to my great-grandmother, Margaret Amy Pyke.

I say I ‘inherited’ this book – it would be more accurate to say that I scavenged it from my granny’s house after she died. It was one object among many liberated from long-jammed drawers and cupboards, tumbled in with children’s drawings made sixty years ago, three dozen too-tight elbow-length silk gloves, half-melted nubs of sealing wax, a tool for working leather, miscellaneous zips, hairnets, hooks-and-eyes. It was not supposed to come to me, in any directed way, but I couldn’t resist it. I can never resist a list.

Isabel Hofmeyr points out that this kind of book, which falls into the category of ‘account books, birthday books, Boy Scout registers, cricket score books’ is less of a book and more of a form. To be more accurate, it’s several forms bound together. It is ‘easily legible, readily surveyable, designed for rapid use rather than extended reading, free from any taint of sedition or obscenity’.1 It is a nice, neat thing. It reminds me a little of the small red Silvine cash books that, as a kid, I’d sometimes buy with pocket money from the corner shop, ruled with columns and lines for income and expenditure, which I’d write over with abandon. I always had the slight sense I was misusing these books but I enjoyed their dimensions and their affordability. I enjoyed, too, the ritual of secreting my private thoughts and hates and wants inside an object which seemed to glow with the promise of an imagined future: a disciplined, grown-up world of offices and bus stops and supermarket sandwiches, of clicking high heels on tarmac, and cold night air.

Margaret is not misusing her form-book though, for the most part. She very properly records bibliographic details according to the columns provided: ‘Title of book’, ‘Author’, ‘By whom reviewed or recommended’, ‘Notes’. And where this content does overspill on to the front and back end papers, there is nothing seditious or obscene about it: a phone number, an address, a shopping list (‘liver, salmon, caviare’).

This book is something to be “used . . . but not authored or read”, as Lisa Gitelman puts it.2 It’s true that Margaret couldn’t be said to have written this book in the way we generally mean when we think of authorship, although she did, in practical terms, write it – or in it. But she does seem to have read the book, in a way: she has marked up entries long after their first appearance, with a little inked or pencilled ‘v’, like a hastily drawn bird, a small ‘o’ – sometimes with a line underneath, sometimes inside another, larger ‘O’, a kind of marginal fried egg – and quite often, throughout, with ‘19/8’, which presumably is 19th August, although which August, exactly, I don’t know.

What the individual marks mean is something I’m still deciphering, like the list itself, which I am slowly transcribing into a spreadsheet. The first entry on the list is H.G Wells’s The Croquet Player. Soon, I’ll look for it, and begin reading it, and then I will write about it here.

Isabel Hofmeyr, Dockside Reading: Hydrocolonialism and the Custom House (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 10.

Lisa Gitelman, Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 25.

Can’t wait!